Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Tactics: Is TV Holding Back The Evolution of Football

The Question: Is television holding back the evolution of football?

From the danger of highlights to celebrity undermining the team, that box in your living room could be shaping the sport's future

There shouldn't necessarily be a point in Cristiano Ronaldo producing skill for skill's sake, but television laps it up. Photograph: Matthew Childs/Action Images

Television is football's demiurge. Depending on your view, it either brought the extraordinary wealth to the English game that allowed the Premier League to become one of Europe's two principal leagues, or it distributed those resources so unequally that the title race has become a procession of the weary old usual suspects. For better or worse, it sets the economics of the game, and dictates the rhythm of the footballing week.

So much is obvious, but what is rarely considered is that television could be shaping the way the game is played, and not necessarily for the better. It sounds, admittedly, a touch far-fetched, but two of football's most respected thinkers believe it to be true, and when Jorge Valdano and Arrigo Sacchi are in agreement, it is usually worth listening.

Killing the pause

For almost as long as football has existed, there have been complaints that it is too quick, that the skills of yesteryear have been supplanted by what, as early as the 1950s, the Austrian journalist Willy Meisl was terming "the fetishisation of speed". The likelihood is that the game will become ever quicker: Roberto Mancini, speaking at a conference in Belgrade, suggested that the tactical development of players was almost at its limit, but that the boundaries of their physical development were only just being pushed.

But for Valdano, the issue of speed is not merely to do with improved understanding of nutrition or physical conditioning. "I heard [the boxer] Carlos Monzón's trainer, Amilcar Brusa, explain that when a boxer fights on television, it's crucial he throw many punches, regardless of where they land," he said. "That's because television demands activity.

"It's the same with football. The game has become more intense than it needs to be. In South America we have the concept of the 'pause' in football, the moment of reflection which foreshadows an attack. It's built into the game, like music, which also needs pauses, drops in intensity. The problem is that this doesn't work in the language of television. A moment of low intensity in a televised football game is seen by some as time to change channels. So the game is getting quicker and quicker because television demands it."

Valdano is a romantic, and is evangelical about the importance of the pause, but here perhaps he has a point. It is probably not so direct a relationship as he makes out, but if television commentary and punditry creates - or at least reinforces - a culture in which thoughtful play is dismissed as boring and harum-scarum running and clattering tackles are praised as representative of the seductive hurly-burly of the Premier League, then ultimately that will have an impact.

The danger of the clip

Ask pretty much anybody to describe England's third goal against Holland in Euro 96, and they will speak of Teddy Sheringham dummying to shoot, then opening his body and laying the ball off for Alan Shearer to smash a controlled slice past Edwin van der Sar and into the top corner. Which is fine, in as much as Sheringham's lay-off demonstrated a fine awareness of his surroundings, great unselfishness and a deft touch, but the move began far earlier, and was glorious in its entirety.

Tony Adams won possession, anticipating and intercepting after Ronald de Boer had miscontrolled a Michael Reiziger clearance. He strode forward, before letting Paul Gascoigne take over 10 yards inside the Dutch half. He switched the ball left for Darren Anderton, and then received the return just in from the left touchline. As Clarence Seedorf closed him down, he rolled the ball back with the sole of his boot, creating room for a jabbed ball inside to Steve McManaman, who played an exquisite chipped return, arcing the ball over Reiziger and into Gascoigne's path as he made a forward charge. Gascoigne showed great strength to hold off Aron Winter, barrelling into the box and drawing Danny Blind before stabbing the ball back with the outside of his right foot to Sheringham, who sensed Johan De Kock closing in and pushed the ball right to Shearer.

The point is that every bit of the move was brilliant, and McManaman's chip to Gascoigne was a technically harder thing to do and displayed greater vision and imagination even than Sheringham's lay-off. But it is forgotten because of television's habit of focusing on the money shot. That is natural and understandable - the point of a highlight, after all, is to take only a few seconds - but the build-up, whether it includes a Valdanista pause or not, is vital, otherwise you end up in Charles Reep territory, focusing only on end results and not the processes by which they are achieved.

More damaging, though, is probably television's habit of focusing on skill: the moody close up of Cristiano Ronaldo performing step-overs or ofZinedine Zidane pirouetting. Skill is a good thing, of course, but it must be focused: there is no point in skill for skill's sake, and when context is removed the sense is lost of why a player produced a trick at that moment.

The danger is that players become focused on their showreels at the expense of the game itself, or that young players learn how to flick the ball over their heads rather than learning about the shape of the game (and shape isn't just a concern of defenders: I went to interview Samuel Eto'o once and found him watching what appeared to be a Middle Eastern league game on television. I asked what it was, to which he replied that he didn't know, but that he would watch any football to study the pattern).

The focus on tricks is a trend only likely to be accentuated by programmes such as Wayne Rooney's Street Striker, and the danger is that football produces a generation of posturing show ponies incapable of producing the incisive pass or making the right run. All young players should remember the example of Sonny Pike, who joined Ajax in 1996 at the age of seven, heralded by numerous clips of him performing complicated keepie-up routines, but never kicked a ball in league football. It is tempting, too, to wonder whether a player such as, say, Danny Murphy has suffered the opposite effect, never quite enjoying the recognition he deserves because he is not flashy enough.

Celebrity and the undermining of system

Sacchi maintains that tactics have not evolved since he led Milan to back-to-back Champions League successes in 1989 and 1990, something he says is "remarkable, worrying". That is possibly an overstatement, for since then 4-2-3-1 has been popularised, 3-5-2 has spluttered into semi-obsolescence, and the false 9 and strikerlessness have flickered towards viability, and yet he is right to the extent that nobody since has been so dedicated to system.

Both Sacchi and Valery Lobanovskyi demanded the sublimation of the individual to the needs of the collective. That took long, hard, boring hours on the training field, and players who were willing to perform unglamorous tasks for the good of the team. In that, Lobanovskyi was probably helped at Dynamo Kyiv by the prevailing ideology, but it was arguably Sacchi's greatest achievement at Milan that, at least initially, he persuaded the likes of Marco van Basten and Ruud Gullit to put their egos to one side.

It seems logical that the increased sophistication of data collection since then should have led to increasingly sophisticated systems, but it has not. For that there are two reasons: firstly, the increased number of games brought about by the expansion of the Champions League has led to a general acceptance of the desirability – probably the necessity – of rotation; and secondly, the increasing self-importance and contractual flexibility of players means many are unwilling to so submit themselves to a manger's demands. Television, of course, has played its part in both developments.

Rotation means that players do not generate the same mutual understanding as they did when teams regularly went unchanged - or switched only a player or two - from week to week. It is far easier for 11 to achieve a mutual understanding when being selected from a basic pool of 15 or so than from 25. An effective system only comes about after months of intensive practice, a factor that hindered both Lobanovskyi and Sacchi at international level.

But it is celebrity players with puffed-up egos and the freedom to walk out on clubs that Sacchi sees as the real problem. "Today's football is about managing the characteristics of individuals," he said. "And that's why you see the proliferation of specialists. The individual has trumped the collective. But it's a sign of weakness. It's reactive, not pro-active."

That, he believes, is the fundamental flaw in the galacticos policy at Real Madrid, where he served as director of football between December 2004 and December 2005. "There was no project," he explained. "It was about exploiting qualities. So, for example, we knew that Zidane, Raúl and Figo didn't track back, so we had to put a guy in front of the back four who would defend. But that's reactionary football. It doesn't multiply the players' qualities exponentially. Which actually is the point of tactics: to achieve this multiplying effect on the players' abilities.

"In my football, the regista - the playmaker - is whoever had the ball. But if you have [Claude] Makélélé, he can't do that. He doesn't have the ideas to do it although, of course, he's great at winning the ball. It's become all about specialists. Is football a collective and harmonious game? Or is it a question of putting x amount of talented players in and balancing them out with y amount of specialists?"

Whether the second galacticos era follows the same path as the first or not, any success they have will be down not to a tactical plan but simply to weight of talent, and it is that which saddens Sacchi. There is a sense that Real Madrid are a side bought not for how they will play together, but how they will look in the next advertisment. That may be a sad reflection of a world increasingly driven by financial demands, but there is a positive: so long as the richest clubs are playing the football of the individual, smaller clubs playing the football of the team still have a chance.

Perhaps it has always been the case that the lust for glamour has sat uneasily with the game's systematisation, but it is hard to avoid the conclusion that Sacchi is right. Football may have developed in other ways, but in terms of a systematised approach demanding self-sacrifice from the components within it, his Milan stands as the evolutionary end-point, and television has played its part in that.

Tactics: Tactics in the Next 10 Years

The Question: How will football tactics develop over the next decade?

The end of the goal poacher and the rebirth of the libero are two trends we are likely to see during the next 10 years

Could we see the death of the classic goal poacher in the next 10 years? Photograph: Peter Robinson/Empics Sport

It is hugely difficult to imagine the future as a radically different place, which is probably why so many visions of the future in the past century have stuck to three basic templates: silver suits and hover-boots; totalitarian nightmare; apocalyptic wasteland. Still, given the way football has evolved in the 146 years since it was codified, it is probably safe to assume that the age of revolutions is over, and that developments in tactics over the coming decade will be incremental rather than radical.

- Inverting the Pyramid: A History of Football Tactics

- by Jonathan Wilson

- 384pp,

- Orion,

- £8.99

The great revolutions – passing, the move from 2-3-5 to W-M; catenaccio; the development of the back four; total football – all sprang up either in response to rule changes, or from a culture with little previous experience of football, and thus a less rigid conception of how it should be played. In the modern world of blanket television coverage, it is almost impossible for football to grow up in the sort of isolation that could allow tactical quirks to develop. As in so much else, globalisation is leading to homogeneity.

Malcolm Gladwell tells the story of Vivek Ranadive, who coached his daughter's team of 12-year-olds into the US's national championships despite having no previous knowledge of basketball. Baffled by the way, as he saw it, basketball teams effectively took turns to attack, Ranadive applied the principles he'd picked up from football and encouraged his side to press the opponent in possession high up the court. I have no idea whether that would be effective at the top level of basketball, but my point is that if there is to be a revolution in football tactics, it will almost certainly come from another sport, or at least from a culture in which another sport predominates.

The possibility of revolution

It always strikes me when reading US and Japanese accounts of football that there is a dislocation, not merely in vocabulary, but in the way of thinking about the game. This is a generalisation, of course, but broadly speaking Europeans view football more as a continuum, the US and Japanese as a series of discrete events. Japanese magazines are full of intricate diagrams that look good but I'm not sure reflect the game as a whole, while I often detect a frustration from US commentators that football doesn't lend itself more readily to the sort of statistical analysis that predominates in American football and basketball.

One of the oddest comments on Inverting the Pyramid came from a US reviewer who expressed surprise that 140 years of tactical history seemed to have produced nothing more sophisticated than moving a player a little bit forward or back, and speculated on the impact an American football offensive or defensive coach might have on football. I would suggest that the anarchic nature of football, the lack of set-plays to be replicated and practised, militates against the sort complex pre-rehearsed moves he was talking about.

But I don't know for sure. It may be that the approach does eventually yield something profound and new and – at the moment – unthinkable, just as Allen Wade, the former technical director of the FA, instituted a new way of thinking about the game when he broke it down into multiple phases for his influential coaching course which produced a generation of coaches that included Roy Hodgson and Don Howe. He faced early opposition for being overly functional but, as the Swedish academic Tomas Peterson puts it, he introduced to football a "second order of complexity", a knowledge of its own working such as Picasso brought to painting or Charlie Parker to music.

Or maybe North Korea, which is about as close as football gets to the Maliau Basin, will take advantage of its isolation to generate something new. The team did, after all, play a 3-3-3-1 at times in World Cup qualifying which, if not revolutionary, is at least unusual. Isolation in itself, though, is not necessarily a good thing, because it often leaves the isolated vulnerable to predators to which the rest of the world has built up immunity – Argentina's humbling at the 1958 World Cup after years of Peronist isolation being the prime example.

The aeroplane model

Whether there is a revolution or not, evolution will continue. Justifying Dynamo Kyiv's switch to 4-4-2 in the mid-60s (which seems to have happened fractionally before Alf Ramsey's similar but independent change in England), Viktor Maslov said: "Football is like an aeroplane. As velocities increase, so does air resistance, and so you have to make the head more stream-lined."

Although the progression has not been straightforward, Maslov has broadly been proved right. Over the past year in the Premier League there has been a turn back towards 4-4-2 (or 4-4-1-1), but single striker systems remain common and in Spain 4-2-3-1 has been the default for some time. At Barcelona – and Arsenal have followed their shape – that itself is being modified, with the two wide attacking players further advanced and the second striker pulled back into a deeper playmaking role to form a 4-3-3.

What is fascinating about Barcelona's 4-3-3 is that while it may look roughly similar to the 4-3-3 of, say, José Mourinho's Chelsea, it has been arrived at via a different evolutionary route (through 4-2-3-1 rather than through the diamond), and so functions in subtly different ways – a useful reminder that tactics are a combination of formation and style and that, as cannot be said often enough, formations themselves are neutral.

Malsov's analogy requires a slight gloss, for to say a team must be streamlined doesn't make a huge amount of sense. What he meant, presumably, was that as the velocity of players increases, it becomes harder for them to find space, and thus more necessary for attacking players to come from deeper positions, making them harder to pick up.

As a general principle that remains true, although we would perhaps say now, having seen the goal-scoring success of Cristiano Ronaldo and Barcelona's forwards cutting in from the wings, that it is advantageous to play with attacking players coming from deeper or wider positions, which rather ruins the image of streamlining. Corollary to that is the use of false nines, centre-forwards who drop deep into a playmaking role, disrupting the opponent's marking scheme, as Lionel Messi did to such startling effect in Barça's 6-2 win at Real Madrid last season.

The two directions of the centre-forward

The false nine is one of two directions in which the centre-forward position seems to be heading (at the highest level – lower down, where control of possession and imagination of approach are necessarily less prioritised, the traditional virtues of being quick or big or predatory are still of value). If he is not refining himself out of existence, he is doing the exact opposite, and imposing himself as a powerful leader of the line and creator of space in the manner of Didier Drogba, Emile Heskey or even Bobby Zamora. Some, such as Dimitar Berbatov and Zlatan Ibrahimovic, combine both styles.

Either way, the situation has emerged whereby a striker's primary function is no longer to score goals, but to create the space for others to do so. Obviously it's advantageous if he can take chances, or even conjure up goals out of nothing, which is what makes Drogba and Fernando Torres so special, but increasingly goals alone are an inadequate measure by which to judge a forward. If the poacher isn't dead yet, he may well be in a decade's time.

Universality (in patches)

That diversification of the striker's role is part of the wider trend towards universality. It was an ideal first articulated by Maslov, before being more fully theorised by Valeriy Lobanovskyi and Arrigo Sacchi, and found its practical form not just at Dynamo and Milan, but also at Celtic in the late 1960s, and at Ajax and Bayern Munich in the 1970s.

The latter three had young teams who, maturing together, grew almost organically to play to each other's strengths and cover each other's flaws, developing a highly fluid style of play. At Dynamo and Milan, it was a conscious policy enforced by visionary coaches. I have my doubts as to whether their rigorously systematised approach is possible in an age of celebrity, but the more general logic of universality pertains.

An analogy can be drawn with table football. Get beyond a certain level, and the key attacking players become the back two because they have time and the space behind them to line up a shot; the three forwards thus take on a function as blockers. As full-backs in football proper have exploited the space they have been afforded and become more attacking, so wide forwards have become more defensive to close them down.

As that has happened, it has become apparent that the player with most space is no longer the full-back, but the second centre-back, which may lead to the return of the libero, something that can already be seen in the performances of Gerard Piqué. With the liberalisation in the offside law stretching the game so it tends to be played in four bands not three, it seems likely that the coming decade will see some elision of the roles of attacking centre-back and holding midfielder, and thus to teams effectively playing with three-and-a-half at the back.

The Hegelian model

Evolution, though, is not linear. It hops about, goes forward and back, and isn't necessarily for the better. Ten years ago, you'd have said football was becoming a game for physical monsters, but the success of the likes of Messi, Xavi, Andrés Iniesta and Andrey Arshavin suggest that while players with the physique of Cristiano Ronaldo clearly have certain advantages, there is still a place for the comparatively diminutive player with skill. And it's worth remembering that 30 years ago the decathlete-turned-full-back Hans-Pieter Briegel was hailed as the player of the future, only to be at least partly responsible for four of the six goals West Germany conceded in the World Cup finals of 1982 and 1986. Size remains something, but not everything.

To an extent, evolution is a game of cat and mouse: a space opens, it is closed, and so a space opens elsewhere. A rugby writer recently suggested to me that rugby World Cups tend not to produce attacking play because of a natural cycle. After each tournament, he said, law variations are brought in to open the game up, which works for a year or two, but by the time the next tournament comes around, coaches have worked them out and so it becomes more defensive again.

It seems to me that, with one or two exceptions – the 1925 change in the offside law, the 1992 outlawing of the backpass and the tackle from behind in response to the sterility of Italia 90 – football is strong enough to generate new ways of attacking on its own without recourse to tinkering with the game's mechanics, but the process of thesis, antithesis, synthesis is the same.

Lurking behind progress, though, are old ideas waiting to be reapplied. Most obviously in the past decade, Greece won Euro 2004 playing with man-markers, setting opponents a problem they had forgotten how to solve. The success Stoke had with Rory Delap's long throws last season fall into a similar category. Teams now have remembered how to counter them, and so they are no longer such a potent threat. It may even be that towards the end of the next decade, as centre-backs have got used to advancing, that the poacher is resurrected as a counter to attacking defenders.

But it seems fair to assume that the recognition of the holistic nature of football – of the team as energy-system, as Lobanovskyi put it – will become more widespread, particularly as statistical analysis becomes more sophisticated and the effects of events in one part of the pitch on events in another are more fully understood. To resurrect an old line, you don't win games by scoring goals, you score goals by winning games: by playing the game where you want it to be played, thus maximising your team's strengths and minimising those of your opponent

Tactics: Nutmegs and the 90s

The Question: How did a nutmeg change football tactics in the noughties?

For the first time in over 30 years, an English side became a world leader in tactical innovation this decade – thanks to Henning Berg being nutmegged

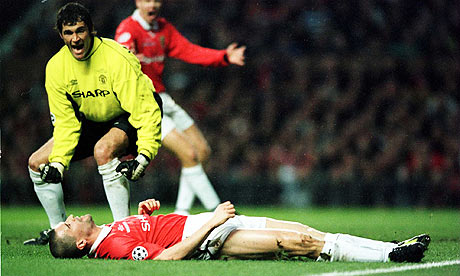

Raimond van der Gouw expresses his frustration at the prostrate Roy Keane after the Irishman's own goal set Real Madrid on the way to a 3-2 victory at Old Trafford that would lead to United transforming their tactics. Photograph: Shaun Botterill/Getty

A little over a hundred days into the new millennium Manchester Unitedsuffered a defeat so striking that it defined the tactical direction of English football for the decade to come. It is rare that you can pinpoint the precise moment at which the world changed, but for Sir Alex Ferguson it did on 19 April 2000 with a 3-2 defeat at home to Real Madrid in the Champions League quarter-final.

This was his equivalent of Liverpool's defeat to Red Star Belgrade in 1973, the game that persuaded him to tear up the old blueprints and start again. Then Bill Shankly, despite having won the Uefa Cup the season before, decided that if Liverpool were to dominate Europe, they had to alter their approach. "We realised it was no use winning the ball if you finished up on your backside," said Bob Paisley. "The top Europeans showed us how to break out of defence effectively. The pace of their movement was dictated by their first pass. We had to learn how to be patient like that and think about the next two or three moves when we had the ball." And so Liverpool changed and, under Paisley, came to dominate Europe in a way no other English side has managed, winning four European Cups between 1977 and 1984.

For Ferguson, too, the decision to change was a tremendous risk. That season his side won the second of three successive Premier League titles, finishing a record 18 points clear of Arsenal in second, while scoring 97 goals in 38 games. The year before they had won the Champions League. There would be many in the difficult seasons of transition who would tell him he should never have changed his approach. His willingness to do so, though, his ruthlessness and clear-sightedness (at least in seeing what was wrong, if not necessarily what the solution was), is precisely what makes him a genius. It is one thing to build a great side; quite another to be brave enough to dismantle it and start again, shaping football's evolution even as you adapt to its changing shape.

The misperception of inadequacy

Yet the strange thing now, looking back at the game, is that United were by no means outplayed. In the Guardian, Jim White spoke of "trademark United huff and puff" being overwhelmed by Real's class, and perhaps that is how it seemed eight minutes into the second half as Fernando Redondo backheeled the ball through Henning Berg's legs, ran on, and crossed for Raúl to tap in his second of the night to make it 3-0.

When a British side loses to a continental team, especially when they are helped to their victory by such a memorable moment of skill, it is natural to reach for the old explanations about the greater subtlety of foreign technique. The fact that Chelsea had been demolished 5-1 in Barcelona the night before probably encouraged the sense of English inferiority in the face of Spanish football. The truth, though, is that United could easily have won the game, perhaps even should have won the game; that their passing and movement, the angles they worked around the box were at least the equal of Real. Besides, the stereotypical lament of English clumsiness hardly tallied with Steve McManaman being arguably the most influential player on the pitch.

This wasn't a case of, say, England against Brazil in 2002, exhaustedly chasing a ball they never quite won back; or of England against Croatia in 2007, doggedly following the Corporal Jones in their heads and launching yet another long ball in the belief that foreigners didn't like it up 'em. This was a very good team playing very good football, and being thwarted again and again by an inspired Iker Casillas and, in one case, by the hand of Aitor Karanka, who seven minutes before half-time, with the score at 1-0, got away with tipping an Andy Cole header over the bar from three yards.

That's not to say United were unlucky – or even that their defeat was predominantly down to ill luck – for Real had dominated the first leg in the Bernabéu, which had finished 0-0, and they benefited at Old Trafford from an unexpected tactical switch by Vicente del Bosque, who had replaced John Toshack earlier in the season. Pulling Iván Helguera deep, almost as a third centre-back, to guard against Dwight Yorke, he both liberated McManaman, who regularly initiated breaks, surging from deep, and the two full-backs, Míchel Salgado and Roberto Carlos, who both got behind United's full-backs again and again. Ferguson eventually matched Real's shape, but by then United were three down, and he admitted he wished he had made the move sooner. "They've never played that formation before," said Ferguson. "I suppose it was a compliment to us, but we were too slow to adjust."

Why United lost

It was a cross from Salgado that led to Real's first, Sávio breaking, exchanging passes with Raúl and moving left, then laying the ball inside for McManaman, who was fouled by Berg. Pierluigi Collina allowed play to carry on as the ball broke for Fernando Morientes, who slipped it into the path of the overlapping Salgado. His cross was low, and Raimond van der Gouw would almost certainly have dealt with it, but either he failed to call or Roy Keane failed to react to the call, and United's captain, lunging to cut the ball out at the near post, diverted it into his own net.

A similar blend of United culpability and Real excellence led to the second and third goals. Perhaps United, aware that Real had the advantage of an away goal, were over-anxious, but they were guilty of overcommitting early in the second half. McManaman broke, and chipped the ball over Mikaël Silvestre, who had come on for Denis Irwin at half-time, for Raúl, who turned back inside the defender and curled the ball into the top corner. His second followed three minutes later with United's defence, seemingly mesmerised by Redondo's nutmeg, sucked to the near post.

David Beckham, negated until then by Roberto Carlos, scored an excellent goal, beating Sávio and Karanka before smacking his finish into the top corner and, even after Paul Scholes had converted an 88th-minute penalty, Yorke had a header saved on the line by Casillas, but three goals was too great a deficit to overhaul. It was those two strikes in three minutes that cost them.

The fatal flaw

So Real were good and United were good, but Real went into a three-goal lead because United had, as the Guardian's subhead said, "lost their heads", perhaps made over-eager by the knowledge they had an away goal to overcome. From Ferguson's point of view, the game followed a worrying pattern. In 1998, after drawing the away leg of their quarter-final against Monaco 0-0, they were eliminated by an away goal. The year before that, a 1-0 deficit from the away leg of their semi-final was rendered insurmountable by Lars Ricken's goal at Old Trafford.

Early goals conceded in the home leg, when played second, had become United's bane, and it's easy to understand why Ferguson should move to guard against the deficiency. It was, in a sense, specifically a European problem: in the Premier League, United could concede early (although obviously the higher quality in confederational competition made it more likely to happen then than in domestic games), and hit back in the reasonable assumption of overwhelming their opponents.

In that 1999-2000 season, for instance, United conceded the first goal and came back to win or draw against Arsenal (twice), Wimbledon (twice), Southampton, Marseille, Everton, Sunderland, Liverpool, West Ham, Fiorentina, Bordeaux, Middlesbrough and Watford. Ferguson would seemingly revel in the fact that "United always do it the hard way", and they were routinely praised for their resilience; perhaps the question, though, should have been why such a dominant team was so leaky.

In the later stages in Europe, not only were sides less easily submerged (yet Real could have been; in the 10 minutes following Real's opener, United had five very good chances), but the consequences were more severe. Over a league season United could afford the odd home draw; in Europe that same draw could mean defeat. And so began the slow, painful, transition towards a lone striker.

The agony of change

The next season the changes were limited to pulling Yorke or Sheringham deeper in Europe and restricting Ryan Giggs's forays. There was a greater sense of caution, which grew after the arrival of Juan Sebastián Verón, and the very obvious switch to 4-5-1, with Scholes or Giggs used as the advanced central midfielder off Ruud van Nistelrooy. The pairing of Scholes and Van Nistelrooy brought the title in 2002-03, but it was only after the arrival of Carlos Queiroz as assistant coach in 2004 that United began to explore more radical alternatives.

As coach of Portugal's youth side, Queiroz was a pioneer of strikerlessness, winning the World Youth Cup in 1989 and 1991 with João Pinto operating as a mobile lone forward, dropping off to create space for Toni, Gil and Rui Costa. For a time he bore the brunt of the anger of fans who had seen a team that had won seven titles in nine seasons with 4-4-2 transformed into a team that won one in five with 4-5-1. But revolution isn't supposed to be easy.

With Wayne Rooney and Carlos Tevez as a front pairing of constant movement, one or both dropping off to create space for Cristiano Ronaldo cutting in, United became part of the tactical avant garde (perhaps almost despite themselves, because had Louis Saha been fit, the swirling trident of unorthodoxy might never have been given its head. The shape could change by the week, with Park Ji-sung and Giggs adding their qualities to a protean mix – sometimes 4-3-3, sometimes 4-2-3-1, often 4-2-4-0 or 4-3-3-0.

It brought a hat-trick of league titles, and two European finals – one won – and Ferguson by the decade's end had his vindication. The idea of 4-4-2 as an absolute default to which English teams had to stick was over, and for the first time since Alf Ramsey's national team lifted the World Cup 1966, an English side was a world leader in tactical innovation.

And if United hadn't let in two goals just after half-time against Real Madrid, it might never have happened. The tactical course of the decade was set when Henning Berg was nutmegged on 19 April 2000.

Tactics:Do Formations Have To Be Symmetrical?

The Question: Do formations have to be symmetrical?

England's lack of a natural left-winger is often seen to be their weakness, but Fabio Capello has turned it into an advantage

The England coach, Fabio Capello, has found a way to combine Steven Gerrard and Wayne Rooney to potentially useful effect. Photograph: Carl Recine/Action Images

England, we keep being told – and the criticism was particularly in vogue after the defeat to Brazil in Qatar, as though a defeat for a side missing 16 potential members of next summer's World Cup squad invalidated two years of progress under Fabio Capello – do not have width on their left side.

They don't, and it doesn't matter. When Capello protests against such designations as 4-4-2 or 4-2-3-1, it is presumably these tiresome arguments he is looking to avoid. Formations are useful, but crude, tools to give a general idea of shape, more relevant to those of us describing the game than those playing it. They are not Platonic ideals to which sides should attempt to live up. To insist that a side playing what we, for instance, call 4-2-3-1, must have a winger on each side is to allow the cart to drive the horse.

England in the World Cup qualifiers found a highly effective way of playing, so effective that they scored six more goals in European qualifying than any other nation (and before anybody argues they had an easy group, remember that no other European group featured three teams who had played at the 2006 World Cup; and that no side had ever beaten Croatia in a competitive fixture in Zagreb until Capello's England went there and shattered their self-belief with a 4-1 win). Just because that way of playing doesn't conveniently fit any default template does not diminish it; in fact, if anything, it may give it greater validity by making it harder to combat.

The Scottish way

Asymmetry has always been part of the game. The earliest extant description of a formation describes how England lined up against Scotland in the first international in 1872. According to notes made by Charles Alcock, the secretary of the FA, England's team was made up of a "goal", a "three-quarter back", a "half-back", a "fly-kick", four players listed simply as "middle", two as "left side" and one as "right side", which sounds like a lop-sided 1-2-7.

The 1-2-7 seems to have been standard, but we have no way of knowing whether it was usual to overload the left. It may be simply that those were the players available to make the long journey from London to Glasgow. Or the shape may reflect the early style of play. Football at the time – at least until Scotland showcased passing in that match – was based on head-down dribbling, with the occasional long ball to clear the lines (hence the "fly-kick"). Assuming a preponderance of right-footers, it may be that they were more effective cutting in from the left towards goal, and it similarly is logical to assume that the natural trajectory for a right-footed fly-kick would be to send the ball on a diagonal towards the left side.

Either way, Scotland held England 0-0, their concern over England's weight advantage leading them to adopt a 2-2-6 and pass the ball to keep it away from their larger opponents. That style slowly spread, and as 2-2-6 became 2-3-5, symmetry ruled, at least in terms of how newspapers presented formations. That changed with the alteration of the offside law in 1925 so that only two defensive players rather than three were needed to play a forward onside, as teams began to withdraw their centre-half into the back-line to give added defensive solidity.

It soon became apparent that that left a side short in midfield, and so, at Arsenal, Charlie Buchan, an inside-right, dropped deep to provide cover; that unbalanced the team, though, and in time the inside-left also dropped, creating the symmetrical 3-2-2-3 or W-M.

The Brazilian re-emergence

The W-M gradually spread through Europe, but it was after it had been exported to Brazil that asymmetry became formalised in a formation for the first time. It was taken across the Atlantic in 1937 by Dori Kurschner, a Jewish former Hungary international fleeing anti-Semitism in his homeland. He became coach of Flamengo, but lasted only a year as players, fans and journalists derided his supposedly defensive approach. Kurschner had replaced Flávio Costa, who stayed on as his assistant, and undermined his boss at every turn, taking advantage of his lack of Portuguese and mocking the new system.When Kurschner was sacked, Costa was reappointed. By then, he had become a convert to the W-M, but having spent 12 months sneering at it, he couldn't admit as much. Instead he came up with what he insisted was a new formation, the diagonal, in which the central square of the W-M was tipped to become a rhombus, with one of the wing-halves slightly deeper than the other, and one of the inside-forwards slightly advanced.

There were those, such as the Portugal coach Cândido de Oliveria, who dismissed the diagonal as nothing more than a repackaging of the W-M, but perhaps it is fairer to say that Costa formalised an unspoken process that was inherent in the W-M. One inside-forward would always be more creative than the other; one half-back more defensive.

At Arsenal in the 1930s, as their former centre-half Bernard Joy explains in Soccer Tactics, the left-half Wilf Copping played deep, with the right-half Jack Crayston given more freedom. When the Wolves and England captain of the late 40s and early 50s, Billy Wright, who could also operate as a centre-half, played as a half-back, did he not play deeper than Billy Crook or Jimmy Dickinson?

Similarly, it was usual – perhaps giving credence to theories linking left-sidedness with creativity – for the inside-left to be more attacking than the inside-right, which is why the No10 rather than the No8 became lionised as the playmaker.

Costa also, whether consciously or not, began the evolution to 4-2-4, his defensive half-back eventually became a second centre-back, and the advanced inside-forward a second striker. Symmetry, briefly, returned, as Brazil won the World Cup in 1958, but by 1962, as others aped their 4-2-4 system, Brazil had moved on, using Mario Zagallo as a shuttling winger-cum-wide-midfielder on the left while Garrincha played as a more orthodox winger on the right: 4-2-4 had become an asymmetric 4-3-3.

Only when Alf Ramsey and Viktor Maslov did away with wingers altogether in the mid-60s did symmetry return, but for another two decades it was still common in those nations where a back-four was usual for one of the wide midfielders to be more attacking than the other. An extreme example came at Newcastle in the early 1980s as they played a 4-3-2 plus Chris Waddle operating on whichever flank he felt featured the weaker full-back.

Intriguingly, away at Chelsea this season, Manchester United played with what was essentially a midfield diamond, with Wayne Rooney as a lone central forward and Antonio Valencia wide on the right, a conscious asymmetry presumably designed to pen Ashley Cole back, a system more defensive in nature but essentially similar to that used by Brazil(and strangely similar to the way Argentina played in the 1966 World Cup, where Luis Artime was the lone centre-forward, and Oscar Más an isolated left-winger). The possibilities of asymmetry are still being explored in the modern game.

The Italian embrace

As the W-M was superseded, football tended to follow one of two paths: there was the Russo-Brazilian, flat back-four model; or there was the Swiss-Italian libero model. Catenaccio abandoned symmetry early.Helenio Herrera's Internazionale featured, in Giacinto Facchetti, a marauding left-back, who was accommodated by having the nominal right-back, Tarcisio Burgnich, tuck in to become a de facto right-sided centre-back. The space he left at right-back was then covered by Jair, the right-winger, chugging back when necessary to cover as a tornante – a returner. The tornante itself can be seen as a development of something that had been characteristic of football in Argentina since the late 1940s and River Plate's La Máquina side.

River's left-winger, Félix Loustau, became known as ventilador-wing (fan-wing) because his back-tracking gave air to the midfield. The centre-half and left-half could then shuffle right, which in turn allowed the nominal right-half Norberto Yácono to take on a man-marking role, tailing the opponent's most creative player (typically the inside-left), secure in the knowledge he would not be leaving a hole on the right side of midfield. The issue was less symmetry than balance.

Gradually Inter's system became formalised and developed into il gioco all'Italiano. "It was effective for a while," said Ludovico Maradei, a former chief football writer of La Gazzetta dello Sport, "and, by the late 1970s and early 1980s everybody in Italy was playing it. But that became its undoing. Everybody had the same system and it was rigidly reflected in the numbers players wore. The No9 was the centre-forward, 11 was the second striker who always attacked from the left, 7 the tornante on the right, 4 the deep-lying central midfielder, 10 the more attacking central midfielder and 8 the link-man, usually on the centre left, leaving space for 3, the left-back, to push on. Everyone marked man-to-man so it was all very predictable. 2 on 11, 3 on 7, 4 on 10, 5 on 9, 6 was the sweeper, 7 on 3, 8 on 8, 10 on 4, 9 on 5 and 11 on 2."

In other words, asymmetries matched, every system mapping neatly on to the one it was pitted against. The problem came when it met an incongruent asymmetry, as was exposed in Juventus's defeat to Hamburg in the 1983 European Cup final. Hamburg played with two forwards: a figurehead in Horst Hrubesch, with the Dane Lars Bastrup usually playing off him to the left. That suited Giovanni Trapattoni's Juventus, because it meant Bastrup could be marked by the right-back Claudio Gentile, while the left-back Antonio Cabrini would be free to attack.

Realising that, the Hamburg coach Ernst Happel switched Bastrup to the right, putting him up against Cabrini. Trapattoni, sticking with the man-to-man system, moved Gentile across to the left to mark Bastrup.

That, of course, left a hole on the right, which Marco Tardelli was supposed to drop back from midfield and fill. In practice, though, Tardelli was both neutered as an attacking force and failed adequately to cover the gap, through which Felix Magath ran to score the only goal of the game.

Symmetry does not equal balance

And that, really, is the advantage of asymmetry; it presents sides with unfamiliar and unpredictable problems. It also takes account of players' individual characteristics. There is something very reductive about the English convention of simply referring to players by position, so that players as dissimilar as Ronaldinho and Steve Stone can both be described as wingers. Other cultures – or certainly those of Italy and Argentina – seem to have a far richer vocabulary with which to describe players, which in turn perhaps leads to greater tactical sophistication as it becomes immediately obvious that setting up a team is not about drilling 10 round holes and hammering pegs into them whatever their shape.

Perhaps that is why it took an Italian to set England up in a coherent way. Capello is not hindered by the dogma that players must play in their best positions, because he does not see players simply as positions (at times it almost feels as though England is stuck in the early 1950s and the days of a selection committee who couldn't conceive of anything beyond a W-M and mechanically voted on who the best left-winger was, who the best left-half was, and gave next to no thought to how they might actually work together).

The thought that Steven Gerrard must play in his natural position through the middle (as though you could somehow pack him and Wayne Rooney into the same space and somehow make twice the impact) isn't a distraction because Gerrard to him is less a central midfielder than a bundle of attributes. Playing him to the left of Rooney allows him into cut in on to his stronger right foot, often arriving late into the penalty area and making him difficult to pick up. Given Rooney has a natural leftward drift, that creates an intriguing interplay that is difficult for defenders to counter.

Attacking width on that flank is provided by Ashley Cole who, as he proved against Arsenal on Sunday, is once again one of the most potent attacking full-backs in the world now that he has been let off the leash by Carlo Ancelotti. Add in Frank Lampard coming from a deeper left-centre position, and England have a diverse range of options from the left, with the more orthodox width of a Theo Walcott or Aaron Lennon on the right.

Perhaps you could quibble that it would be better if, rather than Glen Johnson, England had a more defensively minded right-back, given the lack of cover Walcott or Lennon will provide (although Johnson overlapping as Walcott cuts infield is an attractive prospect), and that in an ideal world Gareth Barry would be right-footed to complement Lampard and cover Johnson's surges. And it would be nice if Emile Heskey, as well as creating space, which he does superbly, could hit a barn door – but those are the sort of flaws that are inevitable in international football, where squads are given not constructed.

England at last have a coherent model of play. That it is not symmetrical is irrelevant; far more important is that it is balanced.

Popular Posts

-

Link It was early in the morning and Anfield stood empty except for one man. Kenny Dalglish had arrived just after dawn, let himself in, hur...

-

Living the dream, the man who stood up to Mourinho The Times Matt Hughes Once a protégé of the Special One, Porto’s successful coach is now ...

-

The Question: is 3-5-2 dead? In the latest instalment of our in-depth series, Jonathan Wilson tracks the rise and fall of a tactical survivo...

-

Source By Daniel Geey. Daniel works as a solicitor for Field Fisher Waterhouse LLP and advises entities wishing to invest in the football in...

-

link by nicodemus I've have been sick and tired of hearig all this JM bashing and saying" hes a cocky twat" " he'll ...

-

Rafa Benitez’s Liverpool Machine July 16, 2010 By Joshua Askew A 7th place league finish and a group stage exit in the Champions League ende...

-

This article is composed of extracts from a very long article intitled: From Sacchi to Zeman, Capello and Lippi to arrive at Descartes and K...

-

Source Get stuck in, readers. Photograph: Peter Dazeley/Getty Images The year of the blog? Very possibly, especially with the current batch ...

-

STEVEN GERRARD EXCLUSIVE The trial changed me. It was frightening. I will never celebrate in a bar again - the Liverpool and England star a...

-

Catenaccio Revisited: Herrera’s Inter October 19, 2010 By Joshua Askew You can’t help but feel sorry for Inter. For one of the biggest clubs...

Labels

Quote of the moment

Defying belief however, is a market Benitez has cornered quite well. The moment you think Benitez is clueless, he defies it by pulling off a result of majesty, like the one achieved in Madrid. The moment he is hailed a genius, he masterminds toothless surrender to a team going nowhere. In the ongoing Anfield power struggle, just when he was cornered by the firing squad, the Spaniard's demise at Liverpool looking practically assured with the ominous suspension of betting by the bookmakers, he squeezes out through a narrow trapdoor and eliminates Rick Parry. Rafa Benitez is Keyzer Soze.- Just Football blog: The Curious Beast that is Football 28 Feb 2009