The Question: Why is pressing so crucial in the modern game?

Barcelona and Bayern Munich both demonstrated the value of pressing the opposition to regain possession quickly last week

After Valeriy Lobanovskyi's Dynamo Kyiv had beaten Zenit Leningrad 3-0 in October 1981 to seal their 10th Soviet title, the report in Sportyvna Hazeta lamented that Viktor Maslov was not alive to see his conception of the game taken to such heights. It's a shame both weren't still with us to have seen those ideas taken to another level again by Barcelona againstArsenal last Wednesday.

As many have noted over the past week, Barcelona's rapid interchange of passes, the relentless attacking and the marauding full-backs perhaps recall one of the great Brazil sides, but the underlying process by which they play comes through the line of Maslov, Rinus Michels and Lobanovskyi.

"Without the ball," Pep Guardiola said after last season's Champions League final, "we are a disastrous team, a horrible team, so we need the ball." It is a sentence that could equally be used of Arsenal: of course they are much better in possession than out of it. The difference is that Barcelona are much better at regaining possession than Arsenal.

After 20 minutes last Wednesday, Barcelona had had 72% of the possession, a barely fathomable figure against anybody, never mind against a side so noted for their passing ability as Arsenal. Their domination in that area came not so much because they are better technically – although they probably are – but because they are better at pressing. In that opening spell, Barça snapped into tackles, swirled around Arsenal, pressured them even deep in their own half. It was a remorseless, bewildering assault; there was no respite anywhere on the pitch, not even when the ball was rolled by the goalkeeper to a full-back just outside the box.

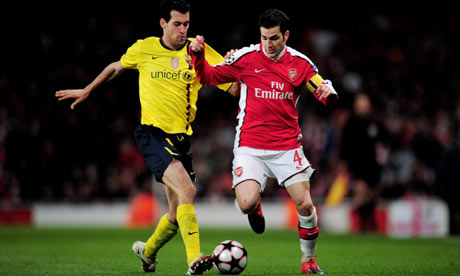

Arsenal buckled. Again and again, even players for whom composure in possession is usually a default gave the ball away. It's hard to believe Cesc Fábregas, who was admittedly possibly hampered by injury, has ever passed the ball as poorly as he did in the first half. Andrey Arshavin was so discombobulated he did a mini-Gazza and crocked his knee lunging at Sergio Busquets.

The psychological factor

This is the unspoken strength of Barcelona: they aren't just majestic in possession themselves; they also make other sides tentative in possession. Think not just of Arsenal, but of Michael Carrick and Anderson haplessly misplacing passes in Rome last May. Partly that is because Barça are so quick to close space; but it is also psychological. Barça are so good in possession, so unlikely to give the ball back, that every moment when their opponents have the ball becomes unbearably precious; even simple passes become loaded with pressure because the consequences of misplacing them are so great.

Although less spectacular in possession, Dunga's Brazil do something similar, aided, as Rob Smyth noted, by having conned the world into believing they still play in a way that they haven't since 1982. That's why so many pundits seem baffled by Brazil's recent successes in the Confederations Cup and the Copa America. John Terry, having watched from the stands as they beat England 1-0 in Doha last year, was still talking about them having "individuals who can frighten anyone one-on-on" while insisting "I don't think Brazil are anything really to worry about".

Their individuals probably aren't, but individuality is no longer their strength; their strength is their cohesion, and the discipline of their pressing which, allied to their technique when in possession, means their opponents almost never have the ball, something Wayne Rooney pointed out in a post-match interview in which his bright red face paid eloquent testament to just how much fruitless chasing he had done.

Notably, Brazil's worst recent performance came in their 1-1 draw in World Cup qualifying away to Ecuador, when only a string of saves from Julio Cesar preserved them from heavy defeat; in Quito, of course, the altitude makes the physical effort required for hard pressing far more difficult.

Shock and awe

Even in the context of their own excellence, though, Barça were exceptional in that opening 20 minutes. Which raises the question of why then, why not every game, and why not in the final 70 minutes. Perhaps an element of complacency crept in, perhaps Arsenal slowly shook themselves out of their daze and began to play, perhaps the replacement of Arshavin with Emmanuel Eboué gave them a greater defensive presence on the right; certainly those seemed to be the commonest explanations.

It is, anyway, a historical truth that when sides strike a period when everything clicks perfectly as it did for Barça in that early period, it rarely lasts more than a few minutes, even in performances held up as the greatest of all time. West Germany, for instance, only really played brilliantly for the first 35 minutes of their 3-1 win over England at Wembley in 1972. Even Hungary, in their 6-3 demolition of England in 1953, were done after 65 minutes, and had dipped towards the end of the first half. Transcendence is, by definition, very difficult to achieve and even harder to maintain.

But it may also be that Barcelona's early surge was part of a calculated plan, and that is why the comparison with Lobanovskyi seems apt, even though the more direct line of influence is through Michels and Johan Cruyff. Pressing with the intensity Barcelona achieved on Wednesday is exhausting, and cannot be kept up for long periods.

In The Methodological Basis of the Development of Training Models, the book he co-wrote with Anatoliy Zelentsov, Lobanovskyi lays out three different kinds of pressing. There is full-pressing, when opponents are hounded deep in their own half; half-pressing, when opponents are closed down only as they cross halfway; and there is false pressing, when a team pretends to press, but doesn't – that is, one player would close down the man in possession, while the others would sit off.

Particularly against technically gifted opponents, Lobanovskyi would have his sides perform the full-press early to rattle them, after which false pressing would often be enough to induce a mistake – and often, of course, his side would be comfortably ahead after the period of full-pressing.

Whether Guardiola has quite such a structured theory is unlikely, but it does seem probable that there was a conscious effort from Barcelona to impose themselves early. The only problem was that, mainly through excellent goalkeeping, and partly through ill luck and poor finishing, Barça were not ahead after 20 minutes, and Arsenal, this season, as their catalogue of decisive late goals suggests, are rather more resilient than they used to be.

Pressing back

Arsenal's attempts to respond with pressing of their own were, frankly, dismal. Allowance should be made for how shaken they were in the early minutes, but the gulf between the sides was still obvious. For pressing to be effective the team must remain compact, which is why Rafael Benítez is so often to be seen on the touchline pushing his hands towards each other as though he were playing an invisible accordion. Arrigo Sacchi said the preferred distance from centre-forward to centre-back when out of possession was 25m, but the liberalisation of the offside trap (of which more next week) has made the calculation rather more complicated.

Again and again, Arsenal's forwards would press, and a huge gap would open up between that line and the line of the midfield. Or the midfield would press, and a gap would open in front of the back four. What that means is that the player in possession can simply step round the challenger into space, or play a simple pass to a player moving into the space; the purpose of the pressing is negated. Or, if you prefer, it was as though Arsenal were false-pressing, without having achieved the first stage of the hustle which is to persuade the opposition you are good at pressing.

Even worse followed after Arsène Wenger apparently attempted to address the issue at half-time, and encouraged his back four to push up. The problem, though, is that if the timing and organisation of the step-up are amiss, a side becomes vulnerable to simple balls over the top such as led to the first goal, or through-balls such as led to the second. This has been a recurring problem for Arsenal over the past couple of years, Gabriel Agbonlahor's goal for Aston Villa at the Emirates last season being a classic example.

The Walcott protocol

What turned the game towards Arsenal – although even in the final 25 minutes when they scored twice, it would be a stretch to say they took control – was the introduction of Theo Walcott. When England beat Croatia 4-1 in Zagreb 18 months ago, he was a key player not just because he scored a hat-trick, but because his pace hit at Croatia's attacking system on their left. At Euro 2008, they had got used to Ivan Rakitic cutting in on to his right foot, with the full-back Danijel Pranjic overlapping, but Pranjic, aware of the danger of allowing Walcott to get behind him, became inhibited. He was neutralised as an attacking threat, while Rakitic became predictable, always turning infield without anybody outside him to draw the full-back – which is the downside of the inside-out winger.

By the nature of how they play, Barcelona, similarly, are vulnerable in thefull-back areas. Dani Alves, in particular, is a sham of a defender – which is why Dunga prefers Maicon – but so long as Barcelona control possession it doesn't matter because his job is to be an extra man in midfield and to overlap for Messi (it may have been fear he would not be able to get forward as usual that led Guardiola to use Messi not on the right but as a false nine).

That is one of the reasons Barça's pressing is so awesome; with the full-backs pushed on, their system often appears as, effectively, a 2-5-3. To press with so many so high is a gamble, but one that has tended to be effective. Florent Malouda's performance against Alves in the second leg of the semi-final last year is an indication of what happens when the gamble fails and Barça do not control possession.

The arrival of Walcott disrupted Barça's pressing because Maxwell, like Pranjic, suddenly began looking over his shoulder (in a similar way, Charlie Davies's diagonal runs behind the full-back were a key to USA's victory over Spain at the Confederations Cup because they prevented Sergio Ramos pushing forward and so made Spain very narrow in midfield).

Samir Nasri had earlier had some success against Alves – almost all Arsenal's attacks in the first hour came through him, or through space he had created – and once Arsenal had weathered Barça's initial surge and begun to have some possession, it may be that Arshavin could have done something similar against Maxwell. Real pace, though, adds another dimension, because it means the full-back knows that as soon as the wide-man has got behind him, he has no chance of catching up. Perhaps that is an argument for Walcott starting, but then again, without Eboué last week, maybe they wouldn't have got any grip on possession.

And that, really, is the dilemma for Arsenal: attack Barcelona where they are vulnerable, by playing two out and out attacking wide-men, and the danger is you never have enough possession to make the most of that potential advantage. Concentrate on winning possession by playing more cautiously, and you may have no damaging way in which to use it.

The bigger problem, though, is the issue of pressing. Even if all else is equal, the fact remains that Barça are far, far more adept at winning the ball back than Arsenal, and that makes it all but certain they will dominate possession, and thus the game. Maslov and Lobanovskyi would have approved.

No comments:

Post a Comment